Understanding Game Theory and Its Impact on Decision Making

- Nagesh Singh Chauhan

- Dec 10, 2025

- 19 min read

Introduction

In an increasingly interconnected and competitive world, decisions are rarely made in isolation. Whether businesses set prices, governments negotiate policies, or autonomous algorithms interact in digital marketplaces, each decision-maker must consider not only their own goals and constraints but also the likely actions of others. This environment of interdependence creates strategic complexity — where the success of one choice depends directly on the choices of others. Game theory, a mathematical framework for analyzing strategic interactions, offers the tools to understand and navigate this complexity.

Originally developed by mathematicians and economists such as John von Neumann, Oskar Morgenstern, and later revolutionized by John Nash, game theory provides a structured way to model competition, cooperation, conflict, bargaining, and coordination. It transforms real-world decision problems into “games” consisting of players, strategies, incentives, and payoffs, allowing us to reason systematically about optimal behavior.

Game theory is far more than an academic subject — it underpins modern economics, shapes policy design, guides competitive strategies, and drives innovations in artificial intelligence, cybersecurity, machine learning, and multi-agent systems. From the pricing wars between firms and the bidding logic behind ad auctions to the behavior of biological species competing for resources, game theory reveals patterns that explain how rational (and sometimes irrational) agents behave when their actions affect one another.

At the heart of this field lies the Nash Equilibrium, one of the most influential ideas in the social and computational sciences. A Nash Equilibrium represents a strategic “steady state” where no player can unilaterally change their decision to achieve a better outcome. In other words, it captures a scenario in which every participant is doing the best they can, given the choices of others. This equilibrium concept has reshaped how economists model competition, how platforms design auctions, and how artificial agents learn stable behaviors in multi-agent environments.

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of game theory fundamentals — from basic terminology and classic game types to deeper conceptual tools such as dominance, payoff structures, strategy spaces, information sets, and equilibrium concepts. The central focus will be a detailed, intuitive, and mathematically grounded understanding of Nash Equilibrium: what it means, how it is derived, why it matters, when it works, and where its limitations lie.

By the end of this article, you will not only understand the mechanics of game theory but also gain practical insight into how strategic reasoning shapes decisions in economics, politics, technology, and AI-driven systems. Whether you are a data scientist, strategist, researcher, or simply someone curious about how rational choices interact, this guide will equip you with the foundational tools to think game-theoretically and analyze real-world strategic problems with clarity and depth.

What is Game Theory?

Game theory is the mathematical study of strategic interaction—a framework for analyzing situations in which the outcome for each participant depends not only on their own decisions but also on the decisions of others. It provides tools to model how rational individuals, companies, or even algorithms make choices when their interests are interdependent.

At its core, game theory helps answer questions such as:

How should competing firms set prices in a shared market?

How do countries negotiate agreements when incentives conflict?

How do bidders behave in auctions with limited information?

How should multi-agent AI systems learn to cooperate or compete?

Rather than assuming randomness or chaos, game theory assumes that players are purposeful decision-makers, each trying to maximize their own payoff. Its strength lies in transforming real-world strategic scenarios—conflict, cooperation, competition, and coordination—into precise mathematical models that reveal likely outcomes, optimal strategies, and stable equilibria.

Key Components of a Game

Every game consists of a few fundamental elements.

1. Players

Entities making decisions — individuals, companies, governments, machine-learning agents, etc.

2. Strategies

A strategy is a complete plan of action.

Pure Strategy: Choosing one specific action.

Mixed Strategy: Randomizing across multiple actions with assigned probabilities.

3. Payoffs

Numerical representation of the outcome (profit, utility, score, reward).Players aim to maximize payoffs.

4. Rules of the Game

This includes:

who moves first,

whether moves are simultaneous,

what information is known,

whether communication or cooperation is allowed.

5. Information Structure

Complete Information: All players know the structure of the game and payoffs.

Incomplete Information: Players lack information about others’ payoffs or types (leads to Bayesian games).

Perfect Information: Players see previous moves (e.g., chess).

Imperfect Information: Players cannot observe all actions (e.g., poker).

Types of Games in Game Theory

1. Cooperative vs Non-Cooperative Games

Cooperative Games: focuses on how groups of players—called coalitions—interact when the primary information available is the overall payoff each coalition can achieve. Instead of analyzing individual competition, it examines how alliances form and how the collective payoff should be fairly distributed among the members of the group.

Non-Cooperative Games: studies how rational, self-interested agents act independently to pursue their own objectives. The most widely used form is the strategic (normal-form) game, where the set of possible strategies and the outcomes resulting from each combination of choices are explicitly defined. A simple real-world illustration of a non-cooperative game is rock-paper-scissors, where each player independently selects an action without coordinating with the other

2. Zero-Sum vs Non-Zero-Sum Games

Zero-Sum: describes a situation where the gains of one party come exactly at the expense of another. The total benefit across all players remains constant—what one player wins, another must lose. Many competitive sports fit this model: one team’s victory directly translates into the other team’s defeat.

Non-Zero-Sum: allows for outcomes in which all participants can either gain or lose simultaneously. In such scenarios, cooperation can create shared value. For example, mutually beneficial business partnerships enable both parties to profit rather than competing for a fixed reward.

3. Static (Simultaneous) vs Dynamic (Sequential) Games

Simultaneous games: require participants to make decisions without knowing what their opponents are choosing at that exact moment. For example, while one company is planning its marketing or product strategy, its competitors are developing their own plans in parallel.

Sequential games: decisions are intentionally sequenced so that one party can observe the other’s move before responding. This staggered structure is typical in negotiations, where one side presents its terms and the other is given time to evaluate them and propose a counteroffer.

4. Symmetric vs Asymmetric Games

Symmetric: the payoffs depend only on the strategies chosen, not on who the players are. This means that if players switch roles but select the same strategies, their outcomes remain unchanged, reflecting identical incentives and options for all participants.

Asymmetric: involve players with different roles, strategy sets, or payoff structures. Swapping positions changes the outcomes because each player faces unique incentives, advantages, or information.

5. Perfect Information vs Imperfect Information Games

Perfect Information: every player has complete visibility into all actions taken previously by other players, as well as the full structure of the game. There is no uncertainty about past moves—classic examples include chess and checkers

Imperfect Information: involve hidden actions or unknown information, meaning players must make decisions without knowing everything their opponents have done or what strategies they may be using. Games like poker or sealed-bid auctions fall into this category.

Core Concepts and Terminology

1. Dominant Strategy

A strategy that always gives the highest payoff regardless of what others do.

2. Dominated Strategy

Always worse than some other strategy.Rational players avoid dominated strategies.

3. Best Response

A strategy that maximizes a player’s payoff given the other players’ strategies.

4. Equilibrium

A stable state where no player has incentive to deviate.

The Nash Equilibrium — The Heart of Game Theory

In strategic decision-making—whether among firms, countries, players, or algorithms—each participant’s optimal choice often depends on what others decide. Game Theory provides a mathematical framework for analyzing such interdependent choices.

At the heart of Game Theory lies the concept of Nash Equilibrium (NE)—named after mathematician John Nash, who introduced it in 1950. Nash Equilibrium helps answer one central question:

“If every player knows the strategies of others and has no incentive to change their own strategy, what outcome will the system settle into?”

Nash equilibrium has become foundational in economics, pricing, auctions, political strategy, AI agents, reinforcement learning, and competitive business environments like hotel pricing.

Formal Definition

A Nash Equilibrium is a profile of strategies—one for each player—such that no player can increase their payoff by unilaterally changing only their own strategy, assuming others keep theirs unchanged.

In simple terms:

You choose the best you can,

Others choose the best they can,

No one regrets their choice.

Nash Equilibrium = Mutual Best Response

Intuitive Definition

You are at an NE when:

You are doing the best given what others are doing.

Changing your decision alone makes you worse off.

No one can “improve” by deviating.

This does not imply:

The outcome is socially optimal

It is the highest revenue/growth state

It is fair or stable long-term

…but it is strategically stable.

Types of Nash Equilibria

1. Pure Strategy Nash Equilibrium

Players choose a definite action (e.g., High Price or Low Price).NE occurs at fixed action combinations.

2. Mixed Strategy Nash Equilibrium

Players randomize over multiple strategies because no pure strategy offers a stable outcome (e.g., Rock–Paper–Scissors).

3. Symmetric vs Asymmetric Nash Equilibria

Symmetric NE: All players choose the same strategy.

Asymmetric NE: Players choose different strategies.

How to Check if a Strategy Pair is a Nash Equilibrium

Take a strategy combination (A’s move, B’s move).

Check if Player A can improve by switching.

Check if Player B can improve by switching.

If neither can improve, it is a NE.

Lets take an example:

Imagine a game between Tom and Sam. In this simple game, both players can choose strategy A, to receive $1, or strategy B, to lose $1. Logically, both players choose strategy A and receive a payoff of $1.

If you revealed Sam’s strategy to Tom and Tom's to Sam's, each would likely maintain strategy A because neither has an option to change to a strategy that would benefit them more. Knowing the other player’s move means little and doesn’t change either player’s behavior. Outcome A represents a Nash equilibrium.

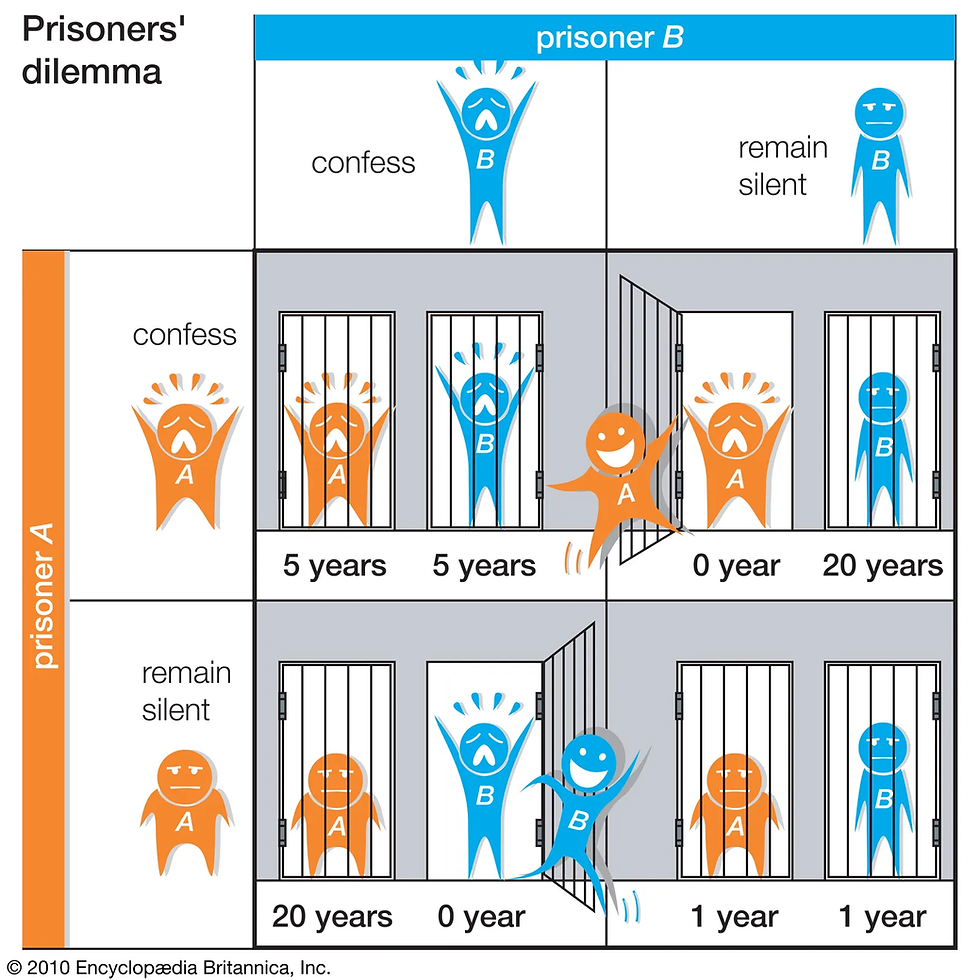

The prisoner’s dilemma– Most Famous Nash Equilibrium

The Prisoner’s Dilemma (PD), introduced by mathematician Albert W. Tucker, highlights the challenges in two-player, noncooperative games. Two suspects, A and B, are interrogated separately and must independently choose whether to confess. They know the outcomes:

If both confess → each gets 5 years.

If both stay silent → 1 year each.

If one confesses and the other stays silent → the confessor goes free, the silent prisoner gets 20 years.

The prisoner's dilemma. Source

Rational analysis shows that confessing is the dominant strategy for each prisoner, regardless of what the other does. Yet this leads to a worse outcome (5 years each) compared to mutual silence (1 year each). Thus, acting in pure self-interest produces a collectively inferior result. This paradox mirrors many real-world situations.

Examples include:

Price wars: Each shopkeeper lowers prices to beat the other, but both end up with reduced profits.

Arms races: Nations keep expanding military capacity and become worse off financially.

Agricultural overproduction: Farmers increase output to gain more individually, but collectively trigger a glut and lower incomes.

One might expect cooperation to emerge if the game is repeated. However, in a fixed number of repeated rounds, backward reasoning shows that defection occurs in every round—starting from the last day where retaliation is impossible.

Cooperation becomes viable only when the game repeats indefinitely and players do not know when it will end. In such scenarios, strategies that reward cooperation and punish selfishness can sustain mutual cooperation.

This idea was demonstrated in Robert Axelrod’s 1980 tournament, where computer programs played repeated PD games without a known endpoint. Strategies classified as “nice”—those that cooperated first and continued cooperating unless betrayed—outperformed all aggressive or deceptive strategies. Among these, “forgiving” nice strategies (which quickly return to cooperation after punishing a defection) achieved the best long-term results.

The Red Queen Effect

The Red Queen Effect is a powerful concept describing situations where competing agents must continuously adapt, not necessarily to gain an advantage, but simply to avoid falling behind. Borrowed from evolutionary biology — named after the Red Queen’s quote in Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass,

"It takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place. If you want to get somewhere else, you must run at least twice as fast as that!”

— the idea fits naturally within the framework of game theory, especially in dynamic, competitive, and evolutionary games.

In game-theoretic systems, especially those involving repeated interactions, unpredictable rivals, or learning agents, the Red Queen Effect emerges as a form of strategic arms race where all players must upgrade strategies just to maintain equilibrium performance.

How the Red Queen Effect Connects to Game Theory

Game theory typically analyzes how rational players behave in strategic situations. While classical solutions like Nash Equilibrium describe steady states, many real-world strategic environments are not static. Rivals adjust, markets shift, algorithms learn, and incentives evolve over time.

The Red Queen Effect captures this dynamic adaptation:

If one agent improves — say, by lowering cost, learning better strategies, or innovating —

Other agents must also improve,

Or they are strategically disadvantaged.

Because every improvement by one player triggers counter-improvements by others, the strategic landscape becomes a continuous evolutionary cycle.

This ongoing escalation is central to fields such as evolutionary game theory, algorithmic competition, and arms-race dynamics in strategic settings.

The Dictator Game

The Dictator Game is a simple economic experiment used to study decision-making, fairness, and altruism. It involves two players: a “dictator” and a recipient. The dictator is given a fixed amount of money (or some valuable resource) and has complete control over how to split it between themselves and the recipient. The recipient has no influence, no decision-making power, and cannot reject the offer. Whatever amount the dictator decides to give is final.

The Dictator Game. Source

Unlike other bargaining games (such as the Ultimatum Game), the Dictator Game removes strategic consequences, because the dictator faces no risk of their offer being denied. For this reason, traditional economic theory predicts that a rational, self-interested dictator would give nothing and keep the entire amount. However, in real-world experiments, many dictators choose to share part of the money—indicating the presence of social preferences such as fairness, generosity, empathy, or inequality aversion.

The Dictator Game is widely used in behavioral economics and psychology to understand human motivations beyond pure self-interest, revealing that people often value fairness or moral norms even when they have full power and no strategic pressure.

The Volunteer’s Dilemma

The Volunteer’s Dilemma is a game theory scenario that highlights the tension between individual self-interest and collective benefit. In this situation, a group faces a problem that can be solved if at least one member volunteers to take a costly action. The outcome is best for everyone when someone steps forward, but each individual prefers that someone else bears the cost instead.

A classic example is an emergency situation: if someone collapses in a crowded place, only one person needs to call for help. Calling is beneficial to everyone (the victim gets aid, and bystanders avoid guilt or blame), but it also carries a cost—time, effort, or possible legal implications—so each person hopes someone else will volunteer. If no one acts, the worst outcome occurs for the group.

The dilemma captures a key insight:

If one person volunteers, the group benefits.

If more than one volunteers, the extra effort is wasted.

If no one volunteers, everyone suffers a collective loss.

This creates a strategic situation where people tend to wait for others to act, leading to inaction even when action is required. The Volunteer’s Dilemma is used to study public goods, emergency responses, social responsibility, and collective decision-making, illustrating the challenges of coordinating beneficial actions in groups where the cost of volunteering falls on a single individual.

Battle of the sexes/ Bach or Stravinsky Game

The Battle of the Sexes game also called Bach or Stravinsky Game is a classic two-player, non-zero-sum coordination game that illustrates how two people can want to act together but disagree on which joint action to take. Both players value coordination and prefer being together over acting alone, yet each has a different preferred activity. This creates a natural tension between mutual cooperation and individual preference, making the game an essential model for understanding strategic interdependence.

The story typically used to explain the game involves a couple deciding between attending a boxing match or the opera. They cannot communicate beforehand but want to spend the evening together. The husband prefers the boxing match and receives a higher payoff if both attend it, while the wife prefers the opera and benefits most when both choose that option. If they fail to coordinate and end up at different venues, both receive the lowest payoff—despite the fact that either coordinated outcome would be better than going alone.

"coordination is beneficial, but preferences differ, and communication is limited."

Because the players make their choices simultaneously, without knowing the other’s decision, the situation highlights the risk of misalignment. The Battle of the Sexes demonstrates how coordination problems can lead to inefficient outcomes and shows why equilibrium concepts like Nash equilibrium are necessary to predict stable solutions where both coordination incentives and individual preferences are balanced.

Imagine two friends, Alex and Jordan, who want to spend Saturday together. They both prefer hanging out over doing things alone, but they disagree on what activity to choose.

Alex’s Preference: Football match

Jordan’s Preference: Art exhibition

They must choose independently, without discussing it beforehand.

Interpretation:

(Football, Football) →Alex gets 2 (their preferred activity), Jordan gets 1.They are together → both somewhat happy.

(Art, Art) →Jordan gets 2 (their preferred activity), Alex gets 1.They coordinate → both satisfied.

Mismatched choices (Football, Art) or (Art, Football) →They go alone → both get 0 (worst outcome).

What This Example Shows:

Both want to coordinate (be together).

Each prefers a different coordinated outcome.

Failing to coordinate hurts both players.

There are two good outcomes—both go to football or both go to art—and two bad ones when they separate. The challenge is that they must choose simultaneously without communication, making misalignment possible.

The Centipede Game

The Centipede Game is a classic sequential game in game theory that illustrates the conflict between immediate self-interest and the potential gains from mutual cooperation. Introduced by economist Robert Rosenthal, it involves two players who take turns deciding whether to “take” the current payoff or “pass” to allow the game to continue. With each pass, the total amount of money or value available to both players increases. If a player chooses to take, they receive a slightly higher payoff than the other player at that moment, ending the game instantly. If they pass, the opportunity shifts to the other player, and the potential rewards continue to grow. The game typically spans multiple rounds, visually represented as a long decision chain resembling a centipede—hence the name.

From a purely rational standpoint, traditional game theory uses backward induction to predict behavior in this game. According to this logic, the last player to move should always take, since it is their final chance to secure a gain. Knowing this, the previous player should also take one step earlier, anticipating that the opponent will take on the next move. Applying this reasoning repeatedly leads to the surprising and counterintuitive conclusion that the first player should take immediately, even though passing would allow both players to earn much more. However, real-world experiments consistently show that people often pass for several rounds, suggesting that trust, cooperation, and bounded rationality play significant roles in actual human behavior.

The Centipede Game is widely used to study issues such as cooperation, trust, escalation, and the limitations of strict rationality. It demonstrates how human behavior can deviate from classical predictions, and it models real-world scenarios like business partnerships, negotiations, and long-term collaborations where ongoing cooperation can create more value than short-term gains.

How the Game Works

Two players move sequentially: at each turn, they choose to Take or Pass.

Taking ends the game, giving the current player a slightly higher payoff.

Passing continues the game and increases the total payoff available.

Payoffs grow as the game progresses, encouraging cooperation.

Backward Induction Insight

Standard rationality predicts the last player will take.

Working backward, each player anticipates the other's future action.

This leads to the prediction that the first player should take immediately.

This outcome is inefficient compared to mutual cooperation.

Why It’s Paradoxical

Immediate taking gives low payoffs compared to continued passing.

Experiments show people rarely take at the first move.

Actual behavior suggests trust, reciprocity, and social norms influence choices.

Reveals limitations of assuming perfectly rational, self-interested players.

Real-World Applications

Business collaborations where long-term partnership yields higher value.

Negotiations where both parties benefit from continued engagement.

Investment rounds requiring patience and trust.

Multi-agent AI or reinforcement learning interactions involving sequential decisions.

Situations where premature defection harms both parties.

Why the Game Matters

Highlights the gap between theoretical rationality and human decision-making.

Provides insights into how cooperation can emerge even in competitive contexts.

Demonstrates the importance of beliefs, trust, and expectations in strategic settings.

Serves as a foundational model for studying dynamic cooperation.

As an example, consider the following version of the centipede game involving two players, Jack and Jill.

The game starts with a total $2 payoff. Jack goes first, and has to decide if he should "take" the payoff or "pass." If he takes, then he gets $2 and Jill gets $0, but if he passes, the decision to “take or pass” now must be made by Jill. The payoff is now increased by $2 to $4; if Jill takes, she gets $3 and Jack gets $1, but if she passes, Jack gets to decide whether to take or pass. If she passes, the payoff is increased by $2 to $6; if Jack takes, he would get $4, and Jill would get $2. If he passes and Jill takes, the payoff increases by $2 to $8, and Jack would get $3 while Jill got $5.

The game continues in this vein. For each round n, the players take turns deciding whether or not to claim the prize of n+1, leaving the other player with a reward of n-1.

If both players always choose to pass, the game continues until the 100th round, when Jill receives $101 and Jack receives $99. Since Jack would have received $100 if he had ended the game at the 99th round, he would have had a financial incentive to end the game earlier.

What does game theory predict? Using backward induction—the process of reasoning backward from the end of a problem—game theory predicts that Jack (or the first player) will choose to take on the very first move and receive a $2 payoff.

The Traveler’s Dilemma

The Traveler’s Dilemma is a well-known game theory scenario that reveals how rational decision-making can lead to surprisingly low-payoff outcomes, even when both players could clearly benefit from cooperating. Introduced by economist Kaushik Basu in 1994, it highlights the tension between individual incentives and collective welfare, similar to the Prisoner’s Dilemma but with a richer payoff structure.

The Story Behind the Traveler’s Dilemma

Two travelers have identical suitcases, both lost by an airline. The airline manager wants to reimburse them but does not know the value of the items inside. Each traveler privately writes down a claim between $2 and $100, representing the value of their lost suitcase.

The rules:

If both claim the same amount, they each receive that amount.

If the claims differ, the airline assumes the lower amount is truthful.

The person who claimed the lower amount receives the lower amount plus a bonus (say, +$2).

The person who claimed the higher amount receives the lower claim minus a penalty (–$2).

This bonus–penalty structure creates strong incentives to undercut the other traveler.

Why the Game Is Interesting?

On the surface, both players would earn the most by cooperatively claiming $100. However, because there is no communication and each wants to maximize their individual payoff, strategic reasoning changes everything.

Game-Theoretic Reasoning (Backward Induction)

Step-by-step logic:

Suppose one player claims $100.The other can gain more by claiming $99 (and receiving $101 = $99 + $2 bonus).

But if $99 is possible, then claiming $98 becomes profitable, and so on.

This downward reasoning continues until the lowest possible claim: $2.

Thus, the unique Nash Equilibrium of the game is:

Both travelers claim $2.

Yet this is the worst possible outcome, far below the cooperative optimum ($100, $100).

Why Rationality Leads to an Irrational Outcome

The Traveler’s Dilemma shows how:

Self-interested reasoning

Without communication

Under competitive incentives

can drive players toward outcomes that are individually rational but collectively poor.

This is known as a race to the bottom.

It demonstrates how backward induction can produce results that contradict intuitive fairness or group benefit.

What Happens in Real Life?

Experimental results show that most people do not play the strict Nash equilibrium strategy:

Many participants choose values above $2, often between $80 and $100.

Human behavior incorporates fairness, cooperation, risk aversion, and a dislike for extreme undercutting.

People tend to reject the pure backward-induction logic.

This makes the Traveler’s Dilemma an important tool in behavioral economics.

Key Lessons from the Traveler’s Dilemma

a. Nash Equilibrium can be inefficient

The equilibrium outcome ($2, $2) is Pareto inferior to all outcomes where both claim higher amounts.

b. Small incentives can cause big strategic shifts

A small reward/penalty (e.g., ±$2) drives players drastically away from the cooperative solution.

c. Human behavior deviates from strict rationality

People often choose higher numbers due to:

fairness norms

expectation of reciprocity

bounded rationality

aversion to destructive competition

d. Useful for modeling price wars

This game resembles competitive markets where firms undercut each other until profits shrink (e.g., airline fare wars).

Real-World Applications

The Traveler’s Dilemma models:

Competitive pricing that pushes margins downward

Race-to-the-bottom behaviors in markets

Bidding wars with penalties for being wrong

Regulation challenges where incentives matter

Cooperation vs. competition in uncertain-value situations

Algorithmic competitive behavior in AI systems

Theory of Moves(TOM)

The Theory of Moves (TOM), developed by political scientist Steven J. Brams, is an alternative framework to classical game theory that focuses on dynamic, sequential decision-making rather than one-shot, static choices. Unlike traditional normal-form games—where players choose strategies simultaneously and remain locked into their choices—TOM models how players can change their strategies over time, anticipating how opponents will respond to each move.

TOM is particularly useful for analyzing real-world strategic interactions where players make adjustments, negotiate, retaliate, compromise, or backtrack. It reflects the reality that decision-makers rarely choose actions only once; instead, they move through a sequence of states, reasoning forward about how those moves will influence future responses.

Why Theory of Moves Was Introduced

Traditional game theory assumes:

Players pick actions once

Outcomes are fixed

Equilibria like Nash Equilibrium describe the end state

However, many real-world interactions involve iterations, reactions, and counter-moves, such as:

Political negotiations

Military escalation

Business competition

Labor–management disputes

Repeated bargaining

International diplomacy

The Theory of Moves captures this dynamic nature by modeling how players transition from one outcome to another through moves and countermoves.

Core Ideas of the Theory of Moves

a. States, Not Just Strategies

TOM focuses on states—specific outcomes resulting from players’ choices.Players can move from one state to another by changing their strategy.

b. Forward-Looking Behavior

Players anticipate how opponents will react not just immediately but over several future moves.

c. Preference for Results of Sequences, Not Single Moves

Players evaluate the final state they expect to reach after a series of moves, not the immediate payoff from one isolated decision.

d. Cycles Matter

If players get stuck moving in circles (state A → B → A → B), TOM allows the game to end in a cycle equilibrium rather than a static one-shot equilibrium.

e. Strategy Changes Are Reversible

Unlike many classical models, players can reverse their actions, acknowledging the real-world flexibility of strategic decisions.

How TOM Works (Simplified)

Start at an initial state based on starting choices.

A player considers making a move to a better state.

The opponent evaluates whether to counter-move.

This continues until:

A stable equilibrium state is reached, or

A cycle is reached where neither player can do better by continuing moves.

Players choose moves strategically, anticipating the entire path, not just the next step.

Key Difference from Nash Equilibrium

Why the Theory of Moves Matters

The Theory of Moves offers several advantages:

More realistic: Most real-world decisions unfold over time.

More flexible: Strategies aren’t fixed; moves are reversible.

More predictive: Better explains cooperation and conflict patterns.

More intuitive: Reflects negotiation, retaliation, and adaptation.

It bridges the gap between static game theory and dynamic strategic behavior, giving analysts a richer toolset for modeling real-life scenarios.

Conclusion

Game theory offers a powerful lens through which we can understand the strategic heartbeat of human interaction. From simple coordination problems to complex sequential decisions, from cooperation dilemmas to competitive arms races, it provides a unifying framework to decode how individuals, firms, governments, and even algorithms behave when their choices intertwine. Through our exploration—spanning Nash equilibrium, the Centipede Game, Volunteer’s Dilemma, Traveler’s Dilemma, the Battle of the Sexes, the Red Queen Effect, the Theory of Moves, and more—we see that strategic reasoning is far richer than static predictions or rigid rationality.

While classical models like Nash equilibrium reveal the stable points of strategic interaction, dynamic frameworks such as the Theory of Moves remind us that real-world decisions unfold over time, through anticipation, adaptation, and response. Games like the Centipede or Traveler’s Dilemma expose the limitations of purely self-interested logic, showing how trust, reciprocity, fairness, and bounded rationality often shape outcomes more profoundly than maximization alone. Conversely, competitive dynamics like the Red Queen Effect illustrate how continuous adaptation becomes essential just to maintain equilibrium.

Together, these ideas paint a vibrant picture: strategy is not only about winning—it is about understanding others, anticipating reactions, balancing incentives, and navigating complexity. Game theory teaches us that the best outcomes often emerge not from isolated brilliance but from harmonizing individual expectations with the strategic landscape in which they operate. Whether we are designing algorithms, setting prices, negotiating agreements, or simply making everyday decisions, game theory equips us with a deeper awareness of the interdependence that defines modern life.

Ultimately, the beauty of game theory lies in its dual power: it simplifies the world enough for us to reason clearly, yet remains flexible enough to capture the nuances of real human behavior. It helps us appreciate that every strategic situation—no matter how simple or complex—is a dialogue of choices, incentives, and expectations. And in that dialogue, understanding the game is often the first step in mastering it.

Comments