LLM-as-a-Judge: Rethinking How We Evaluate AI Systems

- Nagesh Singh Chauhan

- Dec 25, 2025

- 14 min read

Evaluation is the silent backbone of trustworthy AI. LLM-as-a-Judge turns judgment into an engineering discipline.

Generated via ChatGPT

Introduction

Large Language Models have moved far beyond simple text generation. Today, they explain complex ideas, reason through multi-step problems, generate business recommendations, and power autonomous agents. As their capabilities expand, a fundamental question becomes unavoidable: how do we know whether an LLM’s output is actually good? Accuracy alone is no longer sufficient. We care about reasoning quality, relevance, faithfulness to data, clarity, and real-world usefulness—dimensions that are inherently nuanced and often subjective.

Traditional evaluation methods were never designed for this reality. Metrics like BLEU and ROUGE measure surface-level similarity, while human evaluation, though reliable, is slow, costly, and difficult to scale. This creates a widening gap between what modern LLMs can do and how we measure their performance. As LLM-driven systems move into production—supporting decisions, customers, and revenue-critical workflows—this gap becomes a serious bottleneck.

LLM-as-a-Judge emerges as a pragmatic and powerful response to this challenge. Instead of treating evaluation as a rigid comparison against fixed references, it leverages the reasoning capabilities of LLMs themselves to assess quality in a structured, repeatable way. By aligning evaluation closer to how humans judge language—through reasoning, comparison, and contextual understanding—LLM-as-a-Judge provides a scalable foundation for measuring, monitoring, and improving modern AI systems.

Limitations of traditional LLM evaluation techniques

Traditional evaluation models—such as BLEU, ROUGE, Exact Match, and even manual checklists—were built for an earlier generation of NLP systems. While they served well for narrow, well-defined tasks, they struggle to evaluate modern LLM outputs that are open-ended, reasoning-heavy, and context-dependent. Below are the key limitations.

1. They Assume a Single “Correct” Answer

Most traditional metrics rely on comparing a model’s output against one or more reference answers. This works for tasks like translation or classification, but breaks down for LLM use cases where multiple responses can be equally correct. Explanations, summaries, recommendations, and strategies often vary in wording and structure while still being valid. Traditional models penalize this diversity instead of embracing it.

2. Surface-Level Matching Instead of Meaning

Metrics like BLEU and ROUGE focus on token or phrase overlap, not semantic understanding. As a result, an answer that copies reference wording but is shallow or partially wrong can score higher than a well-reasoned, original response. These models measure how similar text looks, not whether it makes sense.

3. No Understanding of Reasoning or Logic

Traditional evaluation models cannot assess:

Logical consistency

Step-by-step reasoning

Whether conclusions follow from assumptions

For modern LLM applications—analytics, decision support, pricing explanations, or agent planning—this is a critical gap. An answer with flawed reasoning but the correct final sentence may pass evaluation, while a logically sound but differently worded answer may fail.

4. Poor Handling of Open-Ended Tasks

Many real-world LLM tasks do not have a clearly defined ground truth:

Summarization

Insight generation

Business recommendations

Conversational responses

Traditional metrics provide false precision in these cases—producing numbers that look objective but fail to reflect actual quality or usefulness.

5. No Concept of Hallucination or Groundedness

In enterprise and RAG systems, the most important question is often:

Is this answer supported by the source data?

Traditional evaluation models cannot detect hallucinations, unsupported claims, or subtle factual fabrications, as long as the output resembles expected text. This makes them especially risky for production systems where trust and correctness matter.

6. Encourage the Wrong Optimization Behavior

When models are optimized against traditional metrics, they tend to:

Mimic reference phrasing

Increase verbosity to boost overlap

Avoid novel or insightful explanations

This leads to safe but shallow outputs and discourages genuine reasoning or creativity—classic reward hacking behavior.

7. Do Not Scale with Human Judgment

Human evaluation captures nuance, context, and usefulness—but does not scale. Traditional automated metrics attempt to replace human judgment, yet fail to model how humans actually evaluate language. This leaves teams stuck between slow but accurate human review and fast but misleading automated scores.

As LLMs evolve from text generators to reasoning and decision-making systems, evaluation must evolve as well. This is precisely the gap that LLM-as-a-Judge is designed to fill.

What is LLM as a Judge?

LLM as a Judge (often abbreviated as LLM-as-a-Judge) is an innovative evaluation technique in the field of artificial intelligence where one Large Language Model (LLM) is used to assess or "judge" the outputs generated by another LLM. Instead of relying solely on human evaluators—which can be slow, expensive, and subjective—this method leverages the reasoning capabilities of LLMs to score, rank, or label responses based on predefined criteria like accuracy, relevance, coherence, or safety. It's particularly useful for scaling evaluations in LLM-powered applications, such as chatbots, question-answering systems, or content generation tools.

The concept gained prominence with the rise of advanced LLMs like GPT-4, where researchers realized that these models could mimic human-like judgment when properly prompted. For instance, in reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF), LLMs-as-judges help align models to human preferences by comparing multiple outputs and selecting the "best" one.

How Does It Work?

At its core, LLM-as-a-Judge follows a straightforward prompting-based workflow:

Define Evaluation Criteria: You specify what makes a good output. This could be "Is the response factually accurate?" or "Does it avoid harmful biases?" These criteria are encoded into a prompt.

Prompt the Judge LLM: Feed the judge model with:

The input query (e.g., "Explain quantum computing").

One or more candidate outputs from the target LLM.

The evaluation instructions.

Example prompt: "You are an impartial judge. Rate the following response on a scale of 1-10 for helpfulness and accuracy, given the query: [query]. Response: [output]. Explain your reasoning."

Generate Judgment: The judge LLM outputs a score (e.g., numerical, binary yes/no), a ranking (if comparing multiple responses), or even a detailed rationale. Advanced setups might involve chain-of-thought prompting to make the judgment more reliable.

Aggregate Results: For large-scale evaluations, results from multiple judge runs (or different LLMs) are averaged or ensembled to reduce variance.

This process can be automated and integrated into frameworks like Amazon Bedrock or open-source tools from Hugging Face, making it easy to run at scale.

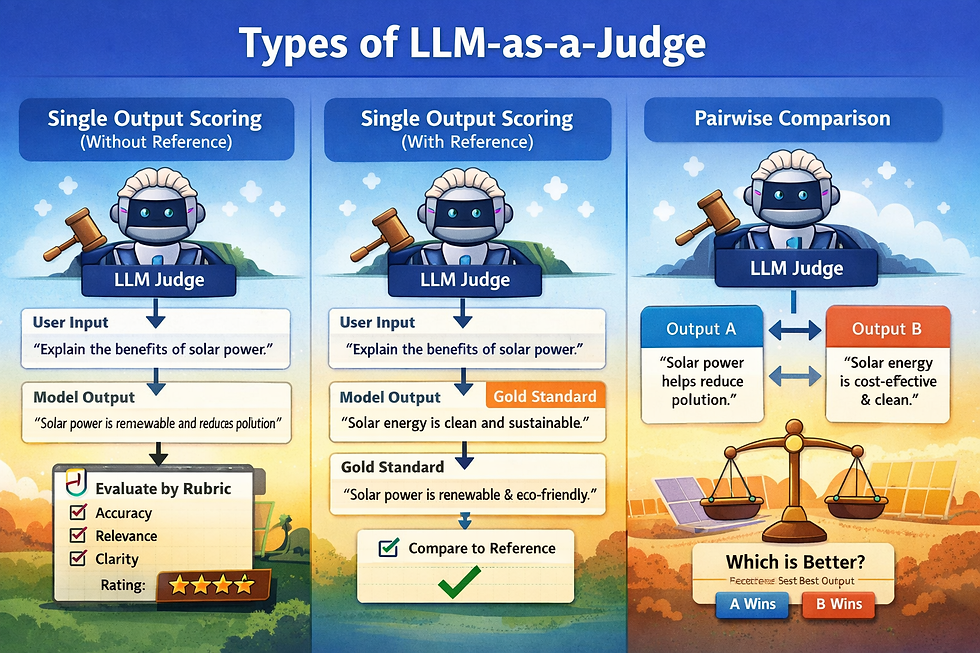

Types of LLM-as-a-Judge

LLM-as-a-Judge was introduced as a practical alternative to human evaluation, which is accurate but expensive, slow, and difficult to scale. Instead of relying on people to manually review model outputs, an LLM can be prompted to act as a structured evaluator, applying consistent criteria across thousands of responses. In practice, LLM-as-a-Judge systems fall into three main types, each suited to different evaluation needs.

1. Single Output Scoring (Without Reference)

In this setup, the judge LLM evaluates a single model response using only the original user input and a predefined rubric. There is no “correct” answer provided. The judge decides how good the response is based on qualities like relevance, factual accuracy, reasoning, clarity, or safety.

Single-Output LLM-as-a-Judge. Image Credits

This approach is especially useful for open-ended tasks where many answers can be valid, such as explanations, summaries, or business recommendations. It mirrors how a human reviewer would assess quality without checking against a solution key.

Best suited for:

Monitoring production responses

Checking reasoning quality and hallucinations

Evaluating RAG answers when no single ground truth exists

Main limitation: Scores can vary depending on the judge’s internal calibration, since there is no reference anchor.

2. Single Output Scoring (With Reference)

This variant adds a gold-standard or expected answer for the judge to compare against. Instead of evaluating the response in isolation, the judge now considers how well it aligns with an authoritative reference. This improves consistency, especially for tasks where correctness matters more than creativity.

Unlike traditional metrics that compare surface text overlap, the judge can assess whether the response captures the meaning and intent of the reference, even if phrasing differs.

Best suited for:

Knowledge-based question answering

Regression testing after model or prompt changes

Benchmark datasets with curated answers

Main limitation: High-quality reference answers are costly to create and may not exist for many real-world tasks.

3. Pairwise Comparison (Most Reliable)

In pairwise comparison, the judge LLM is shown two different responses to the same input and asked to choose which one is better based on defined criteria. Instead of assigning scores, the judge simply expresses a preference.

Pairwise LLM-as-a-Judge, taken from the MT-Bench paper.

This approach is more stable because both humans and LLMs are naturally better at making comparisons than assigning absolute scores. It is widely used in model benchmarking and systems like Chatbot Arena, where outputs from different models or prompts are compared directly.

Best suited for:

Comparing models, prompts, or configurations

A/B testing and benchmarking

Training and evaluating reward models

Why it works so well: Relative judgments are easier, more consistent, and less sensitive to calibration issues than absolute scoring.

The Mathematics Behind LLM-as-a-Judge

LLM-as-a-Judge isn't built on a single, monolithic equation but draws from probabilistic modeling, statistical inference, and optimization techniques rooted in natural language processing and reinforcement learning. At its core, it leverages the transformer-based probability distributions of LLMs to simulate human-like evaluation, often through pairwise comparisons or scalar scoring. The key mathematical foundation is the Bradley-Terry (BT) model for handling preferences, combined with regression and aggregation methods for scores. Below, I'll break it down step-by-step, including derivations and how to compute key elements.

1. Foundational Language Modeling: Probabilistic Token Generation

LLMs like GPT-series are autoregressive models based on transformers. They generate text by predicting the next token via a probability distribution over the vocabulary

Here, ht is the hidden state at timestep t, W is the output embedding matrix, and \softmax normalizes logits to probabilities. For judging, we prompt the LLM with evaluation instructions (e.g., "Compare these responses"), and its output— a preference label, score, or rationale—is sampled or greedily decoded from this distribution. The "math" here ensures the judge's output is probabilistic, mimicking human variability, but we can control it via temperature τ (e.g., lower τ for deterministic scores).

To arrive at a judgment: Prompt the model, decode the output (e.g., via argmax for binary choice), and parse it (e.g., extract "Response A is better" as label 1).

2. Pairwise Preference Modeling: The Bradley-Terry Model

The most mathematically rigorous backbone for LLM-as-a-Judge is the BT model, originally from psychometrics (1952), adapted for LLM alignment via RLHF (Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback). It models the probability that one response y1 is preferred over y2 for a prompt x, assuming each has a latent "reward" or utility score r(x,y).

This derives from the Luce-Shephard choice axiom: Preferences follow a softmax over utilities, assuming Gumbel-distributed noise for stochasticity (explaining why humans sometimes disagree).

How to Derive/Compute It:

In LLM-as-a-Judge, the "judge" LLM simulates this by outputting a preference probability directly (e.g., via prompted logit extraction) or a binary choice, which we treat as a BT sample. For ranking kkk responses, extend to Plackett-Luce (multi-way softmax).

3. Scalar Scoring: Regression and Aggregation

For direct scores (e.g., 1-10 rating), LLM-as-a-Judge treats evaluation as regression to a continuous utility, often prompted with rubrics.

How to Compute:

Generate q questions from output chunks.

For each, P(yes)=σ(logits from judge)

Average: Handles edge cases by weighting (e.g., ∑ P(yesi)/q

This avoids arbitrariness, as scores now trace to countable affirmatives.

Top LLM-as-a-Judge Scoring Methods

As LLM-as-a-Judge matured from an idea into a production practice, several scoring methods emerged to make evaluations more reliable, interpretable, and scalable. Among these, G-Eval and DAG-based evaluation are two of the most influential approaches. They solve different problems, but together they represent the state of the art in structured LLM evaluation.

1. G-Eval (Generative Evaluation)

G-Eval is one of the earliest and most widely adopted LLM-as-a-Judge scoring methods. The core idea is simple but powerful: instead of asking the LLM to give an overall score, you ask it to explicitly reason over predefined evaluation criteria and then assign scores based on that reasoning.

In G-Eval, the judge is guided through:

A clear rubric (e.g., accuracy, relevance, coherence)

Step-by-step consideration of each criterion

A final structured score or verdict

This makes the evaluation process closer to how a human reviewer works—first assessing individual aspects, then forming a holistic judgment.

The overall framework of G-Eval. We first input Task Introduction and Evaluation Criteria to the LLM, and ask it to generate a CoT of detailed Evaluation Steps. Then we use the prompt along with the generated CoT to evaluate the NLG outputs in a form-filling paradigm. Finally, we use the probability-weighted summation of the output scores as the final score. Image Credits

Why G-Eval works well

Encourages deliberate, criterion-by-criterion evaluation

Improves consistency compared to free-form scoring

Produces interpretable explanations alongside scores

Where it fits best

Summarization quality evaluation

Open-ended QA

RAG answer faithfulness

Offline benchmarking and analysis

Key limitation

G-Eval still relies on a single linear reasoning path. If an early judgment is flawed, downstream scores may inherit that error.

2. DAG-Based Evaluation (Direct Acyclic Graph)

DAG-based evaluation takes LLM-as-a-Judge a step further by structuring the evaluation itself as a graph, rather than a single chain of reasoning. Each node in the DAG represents an evaluation sub-task, and edges define dependencies between them.

For example:

One node checks factual accuracy

Another checks groundedness to retrieved context

Another checks logical consistency

A final node aggregates only the validated signals

Because the graph is acyclic, evaluation flows in one direction, preventing circular reasoning and making dependencies explicit.

Why DAG-based evaluation is powerful

Separates concerns: one failure does not contaminate all scores

Enables modular evaluation (plug in / swap out nodes)

Mirrors real production pipelines where checks are staged

More robust for complex, multi-constraint systems

Where it fits best

Agentic systems with tool usage

Enterprise RAG pipelines

Safety- and compliance-sensitive domains

High-stakes decision support systems

Key limitation

DAG-based evaluation is more complex to design and maintain, and requires careful orchestration of evaluation steps.

G-Eval vs DAG: How They Complement Each Other

Aspect | G-Eval | DAG-Based Evaluation |

Structure | Linear, rubric-driven | Graph-based, modular |

Interpretability | High | Very high |

Robustness | Medium | High |

Engineering complexity | Low | Higher |

Best use case | Benchmarking, analysis | Production-grade evaluation |

In practice, G-Eval is often used for model and prompt evaluation, while DAG-based evaluation powers production systems where reliability, debuggability, and control matter.

The Big Picture

Both G-Eval and DAG-based evaluation represent a shift away from “one-number” scoring toward structured judgment systems. G-Eval brings discipline and interpretability to single-judge evaluations, while DAG-based approaches bring engineering rigor and fault isolation to complex AI systems.

The future of LLM evaluation is not a single metric, but a pipeline of judgments, each explicit, testable, and accountable.

Limitations of LLM-as-a-Judge

LLM-as-a-Judge is a powerful and scalable evaluation approach, but it is not a silver bullet. Like any model-driven system, it comes with limitations that must be understood clearly—especially when used in production or for high-stakes evaluation.

1. Judge Bias and Subjectivity

An LLM judge inherits biases from its training data and instruction tuning. It may consistently favor:

Longer or more verbose answers

Confident or authoritative tone over correctness

Familiar phrasing patterns

This means two equally good answers can receive different evaluations based purely on style, not substance. While rubrics reduce this effect, they cannot eliminate subjectivity entirely.

2. Self-Preference and Model Leakage

When the same model family is used as both generator and judge, the judge may implicitly favor outputs that resemble its own style or reasoning patterns. This creates a form of self-preference bias, inflating scores and masking real weaknesses.

Mitigation: Use cross-model judging (e.g., smaller model generates, stronger model judges).

3. Calibration Instability

Absolute scores (e.g., 4/5 vs 5/5) are often poorly calibrated across:

Different prompts

Different domains

Different judges

A “4” in one task may not mean the same as a “4” in another. This makes raw scores unreliable unless tracked comparatively or normalized over time.

4. Susceptibility to Prompt and Rubric Design

LLM-as-a-Judge is extremely sensitive to:

Rubric wording

Prompt framing

Order of evaluation criteria

Small changes in the judge prompt can produce materially different scores. Poorly designed rubrics lead to confident but meaningless evaluations.

5. Risk of Reward Hacking

If models are optimized using LLM-judge feedback, they may learn to game the judge:

Writing answers that look well-structured but lack substance

Overfitting to rubric keywords

Producing “judge-friendly” verbosity

This mirrors classic reward hacking issues seen in RLHF systems.

6. Hallucinated Critiques

While LLM judges can detect hallucinations, they can also hallucinate problems:

Incorrectly flagging correct answers as wrong

Inventing missing context or assumptions

Over-critiquing ambiguous but acceptable responses

This makes blind trust in judge explanations risky without periodic human validation.

7. Limited Ground Truth Awareness

LLM judges do not have direct access to real-world truth unless explicitly provided via context or tools. In knowledge-sensitive domains, a judge may confidently evaluate an answer that is factually incorrect but plausible.

This is especially dangerous in:

Legal

Medical

Financial

Policy-driven systems

8. Cost and Latency at Scale

Although cheaper than human evaluation, LLM-as-a-Judge still adds:

Additional inference cost

Increased latency

Infrastructure complexity

At large scale (millions of evaluations), this becomes a non-trivial operational concern.

9. False Sense of Objectivity

Perhaps the most subtle risk: LLM-as-a-Judge produces numbers and structured feedback, which can create an illusion of objectivity. In reality, these scores remain probabilistic, model-dependent judgments—not ground truth.

LLM-as-a-Judge improves evaluation—but it does not replace critical thinking, human oversight, or domain expertise.

Why Human-in-the-Loop Is Crucial in LLM-as-a-Judge Evaluation

LLM-as-a-Judge enables scalable, consistent, and automated evaluation of language model outputs, but it cannot fully replace human judgment. Evaluation is not just a technical exercise—it encodes values, risk tolerance, and domain understanding.

Without human oversight, LLM judges can drift, misjudge subtle failures, or optimize for the wrong signals. A human-in-the-loop (HITL) setup ensures that automated evaluation remains aligned with real-world expectations.

Humans play several critical roles in LLM-as-a-Judge systems:

Calibration and anchoringHumans periodically review judge outputs to ensure scores mean what they are supposed to mean. This prevents score inflation, drift over time, and misalignment across tasks or domains. Human-reviewed samples act as anchor points for judge behavior.

Detection of nuanced and high-risk errorsLLM judges can miss subtle issues such as misleading logic, regulatory violations, ethical concerns, or domain-specific inaccuracies. Human reviewers bring contextual awareness and risk sensitivity that models still lack—especially in finance, healthcare, legal, or customer-facing systems.

Guarding against reward hackingWhen models are trained or optimized using judge feedback, they may learn to produce outputs that look good to the judge but are not actually useful. Humans help detect these patterns early and ensure that improvements reflect genuine quality gains rather than metric gaming.

Defining and evolving evaluation criteriaRubrics, scoring dimensions, and evaluation priorities are not static. Humans decide what “good” means, which dimensions matter most, and how trade-offs should be handled. LLMs apply rules; humans create and refine them.

Handling edge cases and auditsRare, ambiguous, or high-impact cases should always be escalated to humans. Regular audits of judge decisions help maintain trust, especially as models, prompts, or products change.

The Right Balance

The most effective evaluation systems use humans where judgment is critical and LLMs where scale is required:

LLM judges handle large volumes of routine evaluations

Humans focus on calibration, policy, edge cases, and accountability

LLM-as-a-Judge scales evaluation, but human-in-the-loop safeguards correctness, fairness, and trust.

Rather than replacing humans, LLM judges work best as powerful assistants—amplifying human judgment while keeping evaluation reliable and aligned with real-world needs.

How to Implement LLMs as Judges in Your Workflow

Effectively deploying LLMs as judges requires more than simply adding another model to your stack. It demands clear evaluation goals, thoughtful model selection, and well-defined scoring criteria. In this section, we outline a practical, step-by-step approach to integrating LLM-based evaluation into AI workflows in a way that is both reliable and scalable.

Choosing the Right Judge Model

The foundation of any LLM-as-a-Judge system is the choice of the evaluation model itself. The judge must be well-suited to the type of outputs it is expected to assess.

Key considerations include:

Task alignment: Select a model whose strengths align with your evaluation needs. Some models are better at assessing creativity and stylistic quality (e.g., marketing content or storytelling), while others excel at factual correctness and logical consistency—critical for use cases like content moderation, RAG outputs, or chatbot responses.

Model and provider options: Popular choices include models from OpenAI (GPT series), Anthropic (Claude), and multi-model platforms such as Orq.ai, which provide access to a wide range of LLMs and simplify experimentation across providers.

Cost–performance trade-offs: Balance evaluation quality with operational cost. For early-stage development or large-scale monitoring, lighter-weight or open-source models—such as those integrated through MLflow—can provide cost-effective evaluation without sacrificing reliability.

Defining Clear Evaluation Criteria

A judge is only as effective as the criteria it applies. Clearly defined, measurable evaluation standards are essential for producing consistent and actionable feedback.

Best practices for setting evaluation criteria:

Focus on core quality dimensions: Common metrics include coherence, relevance, informativeness, and factual accuracy. In benchmarks such as Vicuna, minimizing hallucinations—unsupported or incorrect claims—is often a primary concern.

Tailor criteria to the application: Evaluation standards should reflect the real-world context in which the model operates. Collaborate with domain experts to define what “good” looks like for your specific use case, whether that’s essay grading, summarization, or conversational AI.

Customize for user-facing systems: For customer service chatbots, qualitative factors like tone, empathy, and clarity often matter as much as factual correctness. For example, a Vicuna-based chatbot deployed in a customer-facing role may require stronger emphasis on empathy and conversational tone than one used for internal analysis.

Conclusion

As Large Language Models evolve from text generators into reasoning engines and decision-making systems, evaluation becomes the true bottleneck. Traditional metrics fail to capture meaning, reasoning, and usefulness, while pure human evaluation does not scale. LLM-as-a-Judge bridges this gap by transforming evaluation into a structured, repeatable, and scalable process—grounded in rubrics, comparisons, and contextual understanding rather than surface-level similarity.

Yet, the real power of LLM-as-a-Judge lies not in replacing humans, but in augmenting human judgment. Techniques such as single-output scoring, pairwise comparison, G-Eval, and DAG-based evaluation provide complementary signals—ranking quality, explaining failures, and isolating risks. When combined with human-in-the-loop oversight, they form a robust evaluation stack that is both operationally efficient and intellectually honest.

Ultimately, good AI systems are defined not just by how well they generate, but by how well they are evaluated. LLM-as-a-Judge marks a fundamental shift—from brittle metrics to intelligent judgment—laying the foundation for trustworthy, production-grade AI. Used thoughtfully, it turns evaluation from an afterthought into a first-class design principle.

Comments