Context Engineering: From Better Prompts to Better Thinking

- Nagesh Singh Chauhan

- Dec 25, 2025

- 15 min read

Designing the right context is what transforms powerful language models into reliable, grounded, and scalable AI systems. Context engineering shifts the focus from crafting better prompts to engineering how models see, reason, and act.

Generated via ChatGPT

Introduction

Context engineering is what you start caring about the moment your “fun side project” chatbot has to survive contact with real users, messy data, and long-running workflows. It is the difference between a model that dazzles in a one-off demo and one that still behaves intelligently on turn 147, after three tool failures, two contradictory documents, and a user who keeps changing their mind. Where prompt engineering obsesses over the wording of a single request, context engineering obsesses over the world that surrounds that request: what the model should remember, what it should forget, what it should see, and in what format.

Modern LLMs do not suffer from a lack of raw intelligence; they suffer from being asked to reason inside badly designed environments. Dumping entire knowledge bases, full chat histories, and every available tool into the context window is not “smart,” it is a denial of service attack on the model’s attention. The result is familiar: hallucinations promoted to long-term memory, agents stuck in loops, irrelevant tools firing, and answers that read like they were written by an overconfident intern who skimmed the wrong page. Context engineering is the discipline that pushes back against this chaos by treating tokens as a scarce resource, state as a first-class citizen, and every model call as just one step in a larger, carefully orchestrated system.

As context evolves from simple translation to a full representation of the world, AI systems gain deeper understanding while requiring less explicit human guidance. This shift transforms AI from a passive executor into a reliable collaborator—and ultimately a considerate, intelligent partner. Image Credits

This shift has deep implications. Instead of asking “What’s the best prompt for this feature?”, the more powerful question becomes “What is the minimal, most useful slice of the universe the model needs right now?” That leads you to retrieval pipelines instead of static corpora, to compact summaries instead of unfiltered logs, to curated tool loadouts instead of 50-button Swiss Army knives. You begin to design explicit rules for how information is written to memory, how it is later retrieved, when it must be compressed, and how to quarantine or override it when it goes bad. In other words, you stop treating context as a dumping ground and start treating it as your primary product surface.

As context windows grow and tooling improves, this might sound like premature optimization. It isn’t. Larger windows make it easier to shovel junk into the model, but they do nothing to fix the fundamental problems of distraction, conflict, and error amplification. In practice, the systems that feel “magical” to users are rarely the ones with the biggest context; they are the ones where context is ruthlessly curated, aggressively structured, and constantly updated to reflect what actually matters for the next decision. That is the promise—and the challenge—of context engineering, and the rest of this article is about treating it not as a buzzword, but as a concrete, engineerable layer of your AI stack.

What is Context?

To understand context engineering, we first need to broaden what we mean by context. It’s not just the single prompt you send to an LLM. Context is everything the model is allowed to see before it generates a response—the full informational environment that shapes its reasoning.

This typically includes:

System Instructions / System Prompt: Foundational rules that define how the model should behave throughout the interaction. This may include role definitions, constraints, examples, policies, and reasoning guidelines.

User Prompt: The immediate question or task provided by the user.

State / Short-Term Memory: The ongoing conversation history—both user inputs and model responses—that provides continuity and situational awareness.

Long-Term Memory: Persisted knowledge accumulated over time, such as user preferences, summaries of past work, or facts explicitly stored for future use.

Retrieved Information (RAG): Relevant, up-to-date external knowledge fetched from documents, databases, or APIs to ground the model’s response in facts.

Available Tools: Definitions of the actions the model is allowed to take, such as calling APIs, querying databases, or triggering workflows (e.g., check_inventory, send_email).

Structured Output Constraints: Explicit instructions on how the response should be formatted—such as returning a specific JSON schema or table structure.

What is Context Engineering?

Context engineering is the practice of designing and maintaining the full information state around an AI model: instructions, tools, memory, retrieved knowledge, and real-time data flowing into the context window. Instead of fiddling with one “perfect prompt,” you architect a system that continuously curates the right tokens for the next model call.

At its core, context engineering accepts that an LLM is only as good as the information you feed it at inference time, and that the context window is both limited and noisy. The job is to maximize useful signal per token while avoiding failure modes like hallucinations that get written into memory and then worshipped as gospel by the model for the next 200 turns.

In short:

If prompt engineering is writing good questions, context engineering is designing the entire thinking environment.

Why context engineering matters (even with huge windows)

The sales pitch for million-token context is: “Just shove everything in and chill.” The reality is closer to: “Enjoy your extremely expensive, extremely confused autocomplete.”

Several consistent observations show why raw window size is not enough:

Models degrade before the window is “full”: Studies and internal evaluations show correctness dropping well below the theoretical limit (e.g., around tens of thousands of tokens for large models, worse for smaller ones), as the model gets distracted by long histories.

Transformers have a finite “attention budget”: Every extra token participates in quadratic attention, stretching the model’s capacity to track the important pairwise relationships and making long-range reasoning less reliable.

Training distributions favor shorter sequences: Models see many more short contexts than massive ones during training, so they’re simply better calibrated for concise, high-signal inputs.

Long-lived agents generate junk: Agents accumulate hallucinations, outdated tool results, redundant logs, and early wrong guesses in their own context, which then pollute later reasoning unless you actively clean and compress.

Why Prompt Engineering Is No Longer Enough

Prompt engineering thrived in the demo era, not the production era.

Early LLM successes came from clever, single-shot prompts that made models look smart in tightly controlled scenarios.

Once you introduce real users, messy data, and long-running workflows, “just write a better prompt” stops scaling.

Context windows are finite, and attention is fragile.

You cannot shove entire chat histories, document collections, and tool lists into every request without degrading quality.

Long, noisy prompts dilute attention: crucial details get buried among boilerplate, redundant instructions, and stale context.

Missing information guarantees hallucination, no matter how artful the prompt.

A model that has never seen the relevant policy, record, or document will happily invent something plausible instead.

Telling the model “don’t make things up” is not a substitute for retrieving the right facts or calling the right tools.

Different tasks demand different contextual “frames,” not one mega-prompt.

The ideal context for refactoring code is not the ideal context for drafting a legal email or reconciling invoices.

Trying to cover every possible task in one giant instruction block produces vague, conflicted guidance that helps none of them.

Real systems require memory, tools, and governance beyond a single turn.

Production agents must remember user preferences, reuse past decisions, respect organizational policies, and orchestrate tool calls over time.

These behaviors live in state, retrieval, and control logic, not in a single prompt string.

Context engineering treats information as a first-class system asset, not a text dump.

It asks: What is the smallest, most relevant slice of the world the model needs for this step?

It designs how information is stored, retrieved, summarized, filtered, and structured before it ever hits the context window.

Prompt engineering becomes a subset of a larger discipline.

Good prompts still matter, but mainly as the final interface layered on top of well-curated context.

The real leverage comes from deciding what surrounds those prompts—what the model sees, what it remembers, and what it is shielded from.

Prompt Engineering vs Context Engineering

Prompt engineering and context engineering are not rivals; they’re different layers of the same stack. One tunes instructions for a single call; the other designs the information flow over time.

Aspect | Prompt engineering | Context engineering |

Main question | “How do I phrase this request?” | “What total context should the model have right now?” |

Scope | Single request or short exchange. | Full application, long-horizon workflows, many turns. |

Inputs | System prompt, user prompt, maybe a few examples. | Prompts, tools, documents, memories, APIs, schemas, logs, state. |

Core skill | Writing clear, task-specific instructions. | Selecting, structuring, routing, and evolving context. |

Typical failure | Vague, under-specified prompts or brittle “magic words.” | Context overload, distraction, poisoning, confusion, clash. |

Best used for | One-off tasks, content generation, formatting. | Agents, RAG systems, coding assistants, production apps. |

Prompt engineering is “asking better questions.” Context engineering is “designing a better environment” so the model can reason with the right facts, tools, and history.

Example Task

Goal: Recommend a hotel room price for tonight.

Prompt Engineering (Prompt-Centric)

What you do:You try to encode everything into a single, well-written prompt.

Example Prompt:

You are a pricing expert. Based on today’s demand, competitor prices, seasonality, and occupancy, recommend the optimal room price for tonight. Assume demand is high, competitors are priced between $120–$150, occupancy is 85%, and today is a weekend. Explain your reasoning.

What’s happening:

All context is manually stuffed into one prompt

No memory, no retrieval, no tools

If any detail changes, the prompt must be rewritten

Works for demos, fragile in production

Mental model: “Say it better and hope the model reasons correctly.”

Context Engineering (System-Centric)

What you do:You design the environment in which the model reasons.

Engineered Context Stack:

System Context: You are a hotel pricing agent. Use data only from provided sources. Be conservative when uncertainty is high.

Task Context: Recommend tonight’s room price.

Domain Context: Pricing rules, elasticity bands, revenue guardrails.

Retrieved Data (RAG):

Current occupancy: 85%

Competitor prices (live API): $120–$150

Event nearby: Concert with 40K attendance

Memory Context: Last similar event led to 12% revenue uplift.

Tool Context: Allowed tools: price_simulator(), demand_forecast().

Output Constraint: Return JSON: {price, confidence, rationale}

User Prompt:

Recommend tonight’s room price.

What’s happening:

The prompt is simple

The intelligence comes from engineered context

Data is live, structured, reusable

Same system works across thousands of hotels

Mental model: “Design what the model knows before it thinks.”

Key Difference (One Line)

Prompt engineering optimizes how you ask

Context engineering designs what the model sees

Rule of Thumb

If changing the task means rewriting prompts → prompt engineering

If changing the task means swapping context modules → context engineering

Four Core Context Failures

The current literature converges around four ways context goes off the rails: poisoning, distraction, confusion, and clash.

1. Context poisoning

Context poisoning occurs when false or low-quality information enters the context and then gets reinforced as if it were ground truth across future turns. For example, an agent hallucinating a game state, objectives, or API responses and then repeatedly planning around those hallucinations.

Mitigations include:

Validation before persistence: Verify outputs (with checks, secondary models, or rules) before writing them to long-term memory.

Quarantine and threading: Isolate risky hypotheses or speculative plans into separate threads, so failures don’t infect the main trajectory.

Fresh-start fallbacks: When you detect severe inconsistency, spin up a new context seeded with a cleaned summary instead of the full messy history.

2. Context distraction

Context distraction happens when the context becomes so large that the model over-focuses on accumulated history instead of its training priors or the current question. Long conversation logs can make agents repeat patterns from earlier turns instead of adapting to new information.

Key techniques:

Summarization / compaction: Periodically compress conversation and tool traces into concise notes that preserve decisions, goals, and key facts.

Windowed history: Keep the last N high-signal turns plus a compact global summary, instead of the entire transcript.

Separate scratchpads: Move token-heavy details (logs, raw tool outputs) into external memory and re-load only what’s needed, when needed.

3. Context confusion

Context confusion occurs when extra, vaguely related information or tools nudge the model into the wrong behavior, even if that information is not strictly “wrong.” Common examples include agents calling irrelevant tools simply because they exist, or overfitting on an irrelevant snippet of retrieved text.

Mitigations:

Tool loadout management: Use RAG or semantic search over tool descriptions to expose only a small subset (often <30) of relevant tools per turn.

Selective retrieval: Restrict retrieval to task-specific indices and apply reranking and filters, rather than blindly stuffing top‑K chunks.

Schema- and type-aware routing: Route requests to different retrieval or tool pipelines based on intent, domain, or user role.

4. Context clash

Context clash appears when different parts of the context contradict each other—old plans vs new instructions, outdated docs vs updated ones, early wrong guesses vs later evidence. Performance can drop sharply when the model sees multiple conflicting “explanations” and has to reconcile them.

Mitigation patterns:

Pruning and override rules: Newer, higher-confidence information displaces older conflicting content instead of being appended alongside it.

Offloading thinking: Use separate scratchpads or “think” workspaces where agents explore, draft, or reason without polluting the main interaction context.

Structured state: Store state in typed fields (goals, constraints, decisions, open questions) instead of raw text so contradictions are easier to detect and resolve.

The Four Verbs of Context Engineering: Write, Select, Compress, Isolate

A helpful mental model from agent frameworks is that context engineering is mostly four verbs: write, select, compress, and isolate.

Write: externalize context

Writing context means saving information outside the current context window—into state, files, databases, or memory systems—so the agent can use it later without carrying it around every turn.

Common patterns:

Scratchpads: Temporary notes for the current task (plans, TODOs, partial results) stored in agent state, external files, or a memory tool.

Long-term memory: Persistent storage of user preferences, project state, prior analyses, or recurring rules to reuse across sessions.

Structured logs: Capturing tool calls, decisions, and metrics in structured storage (DBs, vector stores) for later retrieval or supervision.

Select: pull in just enough

Selecting context is the act of deciding what to bring into the window from all that external state: memories, tools, documents, previous turns.

Typical mechanisms:

Retrieval (RAG) over documents, code, or prior conversations to fetch the most relevant snippets based on semantic similarity and metadata.

Memory selection to pull in user-specific preferences, episodic examples, or semantic facts based on the current task.

Tool selection via embeddings over tool descriptions or router policies that only expose likely-useful tools per step.

The difference between plain RAG and context engineering is that selection is not just “top‑K nearest neighbors”; it considers task type, trust level, recency, and even cost.

Compress: keep the signal, drop the rest

Compressing context is about retaining only the tokens required for performance and dropping or summarizing everything else.

Core strategies:

Summarization / compaction: Hierarchical or recursive summarization of long histories, large search results, or chains of tool calls into compact representations.

Trimming / pruning: Heuristic removal of old, low-value, or redundant messages and tool outputs without LLM involvement.

Schema-based compaction: Writing compressed context into structured fields (e.g., “current goal,” “constraints,” “architecture decisions”), then regenerating text context from those when needed.

Isolate: separate concerns and state

Isolating context means splitting information and responsibilities so that no single model call has to juggle everything at once.

Patterns include:

Multi-agent setups where different agents own their own tools, rules, and state, and communicate via summaries rather than full transcripts.

Sandboxed environments where code, simulation, or heavy tools run outside the LLM’s context, returning only small, relevant views of state.

State schemas that partition state into fields, only some of which are exposed to the LLM at each turn, keeping the rest as backend-only.

Context Engineering in RAG, agents, and coding assistants

Context engineering shows up differently depending on the application archetype, but the underlying moves are the same.

RAG Systems

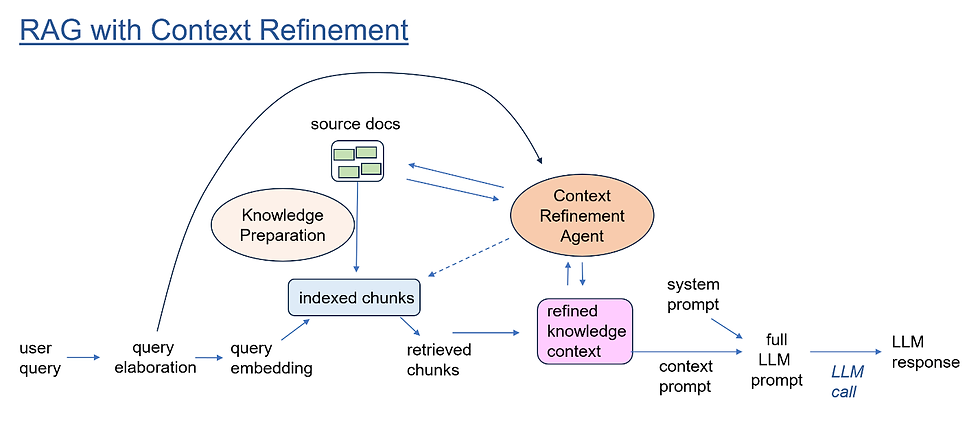

Vanilla RAG takes a query, embedding-searches a vector store, and stuffs the top‑K chunks plus the question into the prompt. Context engineering turns this into a pipeline: route → select → organize → evolve.

Key upgrades:

Routing: Different retrievers or indexes for different domains, modalities, or user types.

Chunking & ranking: Segment docs along semantic or structural boundaries (sections, functions, headings) and rerank by usefulness, not just cosine similarity.

Context evolution: Use feedback and past queries to refine which documents matter and how they are summarized in future interactions.

AI Agents

For agents (LLM + tools in a loop), context engineering is arguably the main job. Agents accumulate message history, tool outputs, plans, and intermediate results over long horizons, which must be constantly filtered and repackaged.

Important patterns:

Just-in-time retrieval instead of pre-loading everything up front; the agent uses tools to fetch what it needs at each step, guided by filenames, schemas, and metadata.

Runtime state and notes for goals, task lists, and persistent decisions across compaction cycles.

Long-horizon techniques like compaction, memory, and sub-agents to survive tasks spanning hours, large codebases, or huge document sets.

AI coding assistants

Coding assistants are context engineering on hard mode: they must understand entire codebases, dependency graphs, and evolving diffs.

Successful assistants typically:

Combine AST-aware indexing, embeddings, and classical search (grep, file names, call graphs) for retrieval.

Maintain project-level memory of architectural decisions, coding style, and past edits, often via special rules files.

Use selective file loading and task-specific context (e.g., only callers/callees and nearby files) instead of dumping entire repos into the window.

Practical design principles

If you’re building real systems (which you are), useful rules of thumb emerge across the different sources:

Optimize for smallest high-signal context, not maximum context size. Treat tokens like RAM on a 90s laptop, not storage on a modern SSD.

Organize prompts into clear sections at the right “altitude.” Use distinct blocks for background, instructions, tool guidance, and output format; avoid both vague slogans and overly rigid pseudo-code in system prompts.

Keep tool sets small and orthogonal. If you can’t tell which tool should fire, the model definitely can’t; redundancies and overlaps invite confusion.

Separate “thinking” from “talking.” Use scratchpads, sub-agents, or offloaded workspaces for exploration so the user-facing context stays clean and focused.

Continuously evaluate context strategies. Use traces, cost metrics, and task evaluations to decide where to add summarization, retrieval refinement, or pruning.

How to start applying context engineering

If you have an existing LLM feature, the incremental path is straightforward:

Instrument and observe: Log token usage, retrieval behavior, tool calls, and failures; look for places where context is large but value is low.

Add basic write–select–compress:

Write: Persist plans, key decisions, and user preferences to an external store.

Select: Build a minimal retrieval layer (even simple embeddings + metadata filters).

Compress: Summarize or trim history once it crosses a threshold.

Harden against the four failures: Add validation before writing to memory (poisoning), prune or summarize aggressively (distraction), filter tools and context per task (confusion), and remove or override outdated info (clash).

Iterate like a performance engineer, not a copywriter: Each change should be testable: does this new summarizer, router, or pruning rule improve accuracy, cost, or latency on your real workloads?

The Role of MCP in Context Engineering

Model Context Protocol (MCP) has quickly become the universal USB for AI applications—enabling plug-and-play access to tools and data sources without building brittle, one-off API integrations. Instead of wiring every model to every system, MCP centralizes interaction and standardizes how context is delivered. As a result, MCP forms a foundational layer of context engineering, acting as a reliable intermediary that transforms heterogeneous data and tools into structured, actionable context for intelligent AI systems.

MCP as the context plumbing layer

Universal interface for context sources: MCP defines a standard way for AI apps to talk to tools, databases, file systems, and services via MCP servers and clients.Instead of bespoke connectors for every API, you expose resources (files, functions, queries) through a single protocol that any compliant agent can use.

From “paste everything” to “request exactly what you need”: With MCP, the agent does not need raw access to entire repos, KBs, or databases; it asks MCP servers for specific resources or operations.This fits context engineering’s core goal: pull precise snippets (a function, a ticket, a row, a config) instead of flooding the context window with whole files or tables.

Structuring and constraining context

Structured responses instead of text blobs: MCP tools return structured JSON (or similar) that can be transformed into compact, high-signal context blocks for the model.This reduces noise, enables selective inclusion of only relevant fields, and makes it easier to summarize or cache results across turns.

Security and governance baked into context access: MCP sits between the model and sensitive systems, enforcing permissions, auth, and scoping on what can be retrieved or modified.Context engineering then operates on approved slices of data, aligning “what the model sees” with organizational policy by construction.

Enabling tool- and memory-rich agents

Standardized tool ecosystem for agents: MCP lets you plug in many tools (code search, DB queries, ticketing, logs) behind one protocol, instead of unique wiring per tool.This lets context engineering focus on tool selection and routing (which tools to expose per task) rather than low-level integration pain.

Better long-horizon context management: Because MCP tools can fetch files, state, and prior outputs on demand, agents can keep their prompts small while storing most context off-window.Compaction, note-taking, and retrieval strategies described in context-engineering guides map naturally onto MCP-backed resources instead of fragile, in-prompt history.

MCP’s big-picture role in context engineering

MCP is the “I/O layer” of context engineering: It standardizes how agents read and write the external world — tools, data, memory — so context strategies are portable and reproducible across models and platforms.

Context engineering is the “policy and strategy layer”: It decides which MCP resources to call, when, and how to turn their outputs into high-value tokens inside the model’s window.

Together, MCP gives you clean, composable access to context, and context engineering tells you how to use that access without drowning the model in it.

Multi-Modal Context Processing

Multi-Modal Context Processing extends context engineering beyond text by incorporating signals from multiple modalities—such as vision, audio, structured data, tools, and environmental state—into a single, coherent context. As highlighted in the paper, real-world interactions are inherently multi-modal, and relying on language alone increases ambiguity and human effort. Context engineering therefore focuses on how these diverse inputs are aligned, filtered, abstracted, and combined into machine-interpretable representations that models can reason over effectively.

An example workflow for processing multimodal context with hybrid strategies. Credits

Key aspects of multi-modal context processing include:

Context fusion: Integrating text, images, audio, sensor data, and structured signals into a unified contextual view.

Alignment & synchronization: Ensuring different modalities refer to the same entities, timeframes, and scenarios.

Relevance prioritization: Selecting which modalities matter most for a given task to avoid context overload.

Abstraction & compression: Converting raw multi-modal inputs into low-entropy, reasoning-ready representations.

Grounded reasoning: Enabling models to anchor decisions in real-world signals, reducing hallucination and interaction cost.

Conclusion

Context engineering represents a fundamental shift in how we build intelligent systems with large language models. As our discussion shows, the reliability and usefulness of an LLM no longer depend primarily on clever prompts or ever-larger models, but on how well we design the contextual environment in which the model reasons. By deliberately structuring system instructions, task definitions, domain knowledge, memory, retrieved information, tools, and output constraints, context engineering transforms raw model capability into consistent, grounded, and controllable intelligence. In this sense, most real-world LLM failures are not model failures, but context failures.

Looking ahead, context engineering will increasingly define the boundary between experimental demos and production-grade AI. As systems evolve toward multi-modal, agentic, and collaborative intelligence, the ability to collect, manage, and use context effectively will become a core engineering discipline—on par with model training itself. Standards like MCP, advances in multi-modal context processing, and human-in-the-loop evaluation frameworks will further reduce ambiguity and interaction cost, enabling AI systems to move from instruction-followers to reliable collaborators. In the future of AI, models may power intelligence—but context engineering will determine whether that intelligence is trustworthy, scalable, and truly useful.

Comments